January 30, 2026

Photo

Mathieu Larone

January 30, 2026

Photo

Mathieu Larone

People who trust their neighbours report a higher quality of life. That’s the takeaway from a 2023 infographic by Statistics Canada, highlighting both a growing problem—the “loneliness epidemic” that has public authorities concerned—and a potential solution.

The numbers are clear: 2024 Canada-wide statistics show that 13.4% of the population “always or often” feel lonely, while 28% of Quebec respondents reported feeling lonely “sometimes or often” in 2023. Behind these figures lies an alarming reality: many people feel increasingly isolated. This loneliness has serious and wide-ranging repercussions that include depression, chronic illness, gambling addiction, and alcoholism. Many medical professionals even compare the health effects of loneliness to those of smoking. Anyone want a drag?

Who—or what—is to blame? It’s easy to point fingers at the internet and social media, which are often held responsible for all society’s ills. But a 2024 study from the American Psychological Association identifies another culprit: “Cultural norms in the U.S. are often characterized by individualism [...] declining social connections and increasing political polarization.”

Today, many sociologists are chiming in to make people consider another, often-neglected factor: the layout of our cities.

Nothing brings out the misanthrope in me quite like being stuck in rush-hour traffic. Trapped in my metal box, stressed by the speeds and rapid-fire demands of driving, I get exasperated by every mistake my fellow motorists make. Only when I pull into a parking spot can I finally breathe easy again. It never ceases to amaze me that even after so many years behind the wheel, driving still manages to put me in such a foul mood.

I try to remember the last time a walk made me feel that way, and draw a blank. Even after 20 years in my neighbourhood, a stroll around the block remains a source of constant wonder.

As I wend my way through streets I know so well, I check if my elderly neighbour’s steps are clear of snow and straighten the books in the little free library. I say hello to the woman who lives two doors down and her daughter on their way home from school. Unlike the grinding resentment that takes hold of me when I drive, walking allows me to form casual bonds with all kinds of people. I’m not alone in this experience. Study after study shows that collective well-being grows from these fleeting encounters. Yet since the 1950s, the trajectory of urban development has focused on keeping us apart. Our highways have widened, our houses have gotten bigger and bigger, and so too have our cars. It’s the American Dream: a house and a yard for every nuclear family.

“As we move to the suburbs, once-communal spaces are subsumed by the private realm,” explains Guillaume Éthier, professor in the Department of Urban Studies and Tourism at Université du Québec à Montréal.

The result? Public pools empty out, neighbourhood movie theatres shut down, and everyone stays home, not talking to anyone.

These trends distance us from essential public spaces—and, with them, the potential for chance encounters. As part of a study on the impact of pedestrian-only streets, Éthier measured encounters between strangers. Nearly 15% of those surveyed had not only met new people, but had cultivated those connections to the point of developing a friendship. His findings prove that the daily act of rubbing shoulders with new people truly can expand our social network.

“Cities change slowly,” muses Karl Dorais Kinkaid, an urban planner at Enclume, a workers’ co-operative. “Even if people demand more public spaces, they won’t spring up overnight.” In practice, the transition from a grassroots idea to a completed project often takes years. And suburbanization has left a legacy of neglect. As Kinkaid puts it, “We have to make up for 50 lost years.”

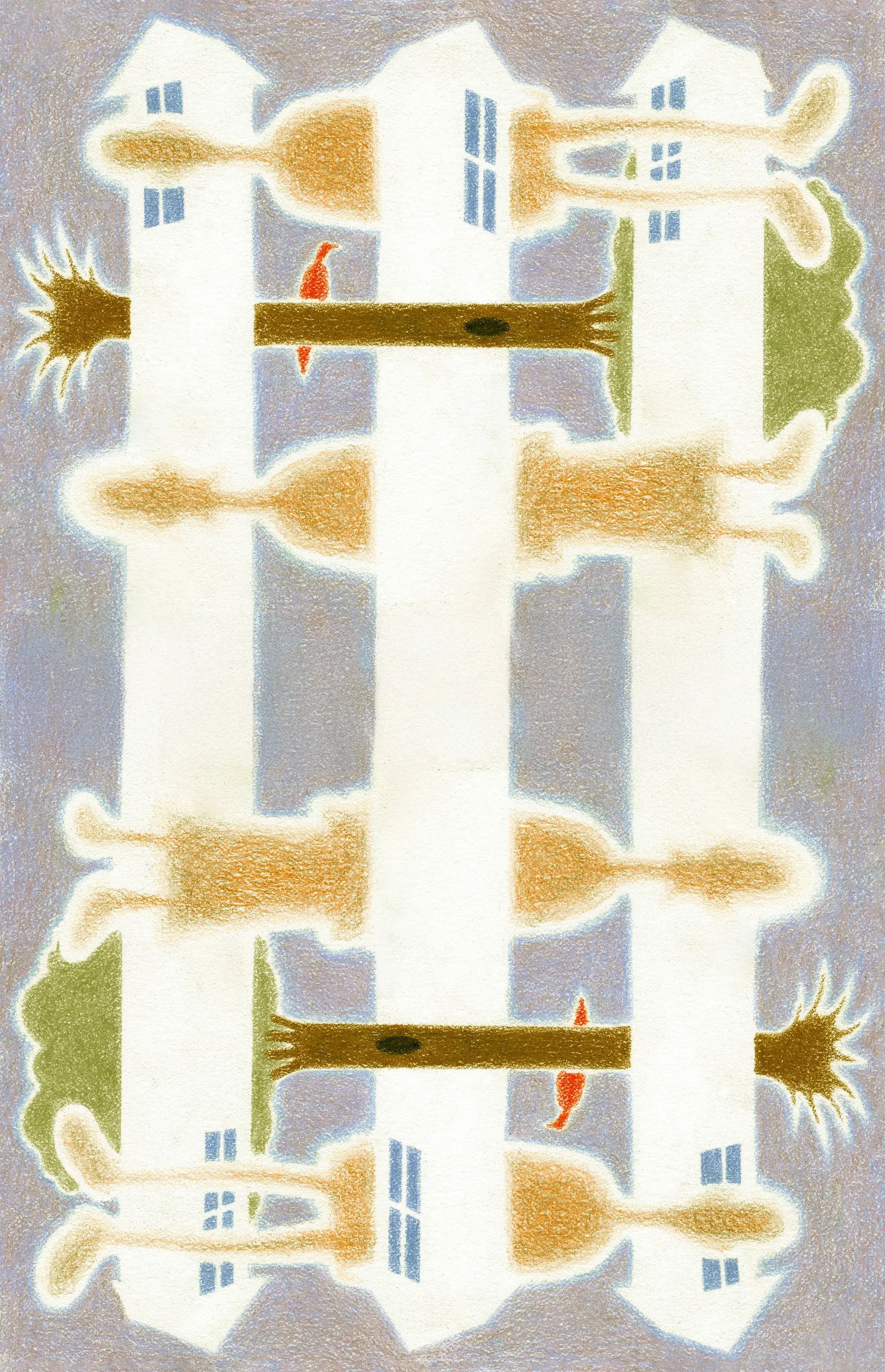

Solutions must be imaginative and flexible. For Guillaume Éthier, placemaking—a broad term that encompasses initiatives like green alleys and organizing cultural activities on pedestrian streets—represents a promising brand of “flexible urban planning.”

Mathilde Falgueyret, an urban planner with Ædifica, reminds us that public art also serves as a strong social glue. “Culture nourishes urban space,” she says. “Art creates a shared culture and a sense of belonging. But that’s not all: a work of art can transform the atmosphere of a place, turning it into a worthwhile destination for a stroll.”

And while poor urban planning contributes to individual isolation, curing the loneliness epidemic will require a multi-pronged approach. Perfectly designed public spaces aren’t a magic bullet that will solve every problem. “Simply creating public spaces won’t automatically get people out using them,” notes Guillaume Éthier. “People have to want to forge ties and build communities.”

If we want to win the fight against loneliness, we’ll have to build a more communal future. With authoritarianism on the rise, fostering supportive communities is one way to protect our freedoms. The true importance of social ties comes into focus when times get tough. Our relationships with others are a fundamental part of collective resistance, and they can also make us more resilient as we move forward toward a brighter future—together.