December 9, 2023

Photo

Renaud Lafrenière

December 9, 2023

Photo

Renaud Lafrenière

Khoa Lê is generous, frank, and radiant.

Filmmaker, visual artist, restaurant owner, and co-founder of the sex-toy company Afterglo, Lê believes that his professional eclecticism is the product of his ADHD. But despite his many accomplishments, Lê prefers to define himself as Vietnamese, an immigrant, a friend, son, brother, uncle, or colleague. He’s less interested in professional titles than the creativity that flows from authentic connections between human beings.

Whether he’s staging the daily life of his grandmother in his acclaimed documentary Bà Nôi or orchestrating a dinner with friends, Lê believes that magic is at work in each encounter, in the intimacy of daily life, in the invisible, and in the small gestures of tenderness when arms touch over a hotpot.

Catherine Métayer, BESIDE’s Editor-in-Chief, met him at Café Pastel Rita in Montréal just after his visit to BESIDE Habitat in Lanaudière with two members of the team from Denise, his beloved restaurant and wine bar: sommelier Morgane Muszynski and chef Marc Villanueva.

Being both foreign and familiar in a place is a feeling I have all the time. I feel really at home in Québec. I arrived here when I was five years old, and still there are so many times when I feel like a foreigner. I don’t understand certain codes. I don’t agree with certain ways of doing things, and I know this comes from my culture of origin.

When I go to Vietnam, it’s the same thing. So many gestures and places there are so familiar to me: spaces, ways of arranging things. An incongruity in spaces. A pragmatic rather than aesthetic logic that I like. It feels like this speaks to me because I was born there.

It’s a film about intimacy. I enter the daily lives of several couples and individuals: trans women, lesbian couples, gays, queers, younger people who identify as non-binary, older people who are in more heteronormative models.

My film is made up of a series of short scenes, without incidents, without a narrative arc. My approach is more sensory. I touch on family, affiliation, and memory.

In the case of those who’ve been abandoned by their families, I also ask: What is left of the relationship to home? Where do we exist when we have a roof, but no family? Several trans women, for example, have recreated a home with other trans women. I observe them a little like an anthropologist.

Do I set the table or will we set the table together? Running a restaurant is the same thing. What will we eat? What will we drink? What’s the service like? What’s the tone? These are choices of staging, of physical relationships and human connections.

Afterglo takes us into the depths of subjects I have a profound interest in, linked to emotion, sensuality, and intimacy. These are things we didn’t talk about at home.

Beyond physiognomic pleasure, what I’m interested in once again is our relationship with others. How to build a relationship of intimacy with each other. Through our toys, I develop tools for communication to lead people (secretly) to step outside established norms and communicate differently.

Lack of sexual education is widespread in our society. We’re taught to put condoms on bananas between two jokes. But that’s not intimacy.

We live in a society of consumption. Everything is disposable. I need you; I don’t need you anymore. We don’t spend time thinking about the invisible, or really about relationships. We don’t spend time thinking about our colleague who’s had a strange look on his face for two weeks. It’s too much for us.

In my culture in Vietnam, we’re not good with words, but we’re very good with gestures. We don’t openly say, “I love you,” but we make very tender gestures.

Yes, I have a main quest: connection and reconnection. How do we recreate relationships that have been lost, eroded, or cut off? How do we reconcile with a friend or a parent? Or how do we keep up a relationship?

In this film, I reconnect with [my grandmother], a human being who’s so far away from me. She really bugs me sometimes [laughs]. And yet, I can’t live without this person. She’s my anchor. Here we are again in this contradiction between the foreign and the familiar. She bugs me, but the bonds that link us are intangible and unconditional.

This is super important. We can’t just insert ourselves into life from point A to point Z. It’s a continuity, otherwise our existence is meaningless: we’re just killing time, doing business between A and Z and having feelings of happiness and sorrow.

For example, if I go to a café, I’ll meet someone. This person might tell me something that changes my life. I’ll talk about it with a friend. It will shake up her life, and so on and so on. This is how our stories end up intersecting. Our individual story is part of a familial and collective story.

If, as young people, we aren’t in touch with our grandparents, we don’t evolve as humans, we don’t develop our emotional memory. We have to celebrate our elders like treasures. They’re not at the end of their lives, they’re at the height of their experience and wisdom. They have something to teach us.

My film is partly about that. My grandmother has something to teach me in her way of being. For me, daily life, the everyday, is the key to understanding so many things.

Cooking is the thing that gets me to drop everything. Because your body is in motion: you become aware of each movement. Opening a package, cooking pasta … there’s something so meditative in it.

I’m not talking about cooking in a purely functional way, but creating a solitary moment for ourselves, or sharing the moment with others. And for me, because I cook a lot of Asian food, it definitely allows me to connect directly with a culture that’s far away from me, that’s not part of my daily life.

So each time I cook, I bring these memories into my home. And I love eating foods that are meant to be shared, because your body becomes part of it. Hotpots, for example, or Korean or Japanese barbecue.

My job is to create a culture for the business. After that, the decor and all the rest is secondary. I try to create an open space where employees can come and say: “I have an idea.”

There’s a little bit of punk in Denise, because I refuse to accept it if someone says, “that doesn’t fit here.” It fits because there’s a human being who thinks it’s pretty. This human being inhabits this space, so it fits.

I like the incongruous side of Vietnam. At Denise, I give myself this liberty. Incongruity can exist in this space. Every space in Montréal resembles all the others. We don’t invent anything, anyway, so why not have fun?

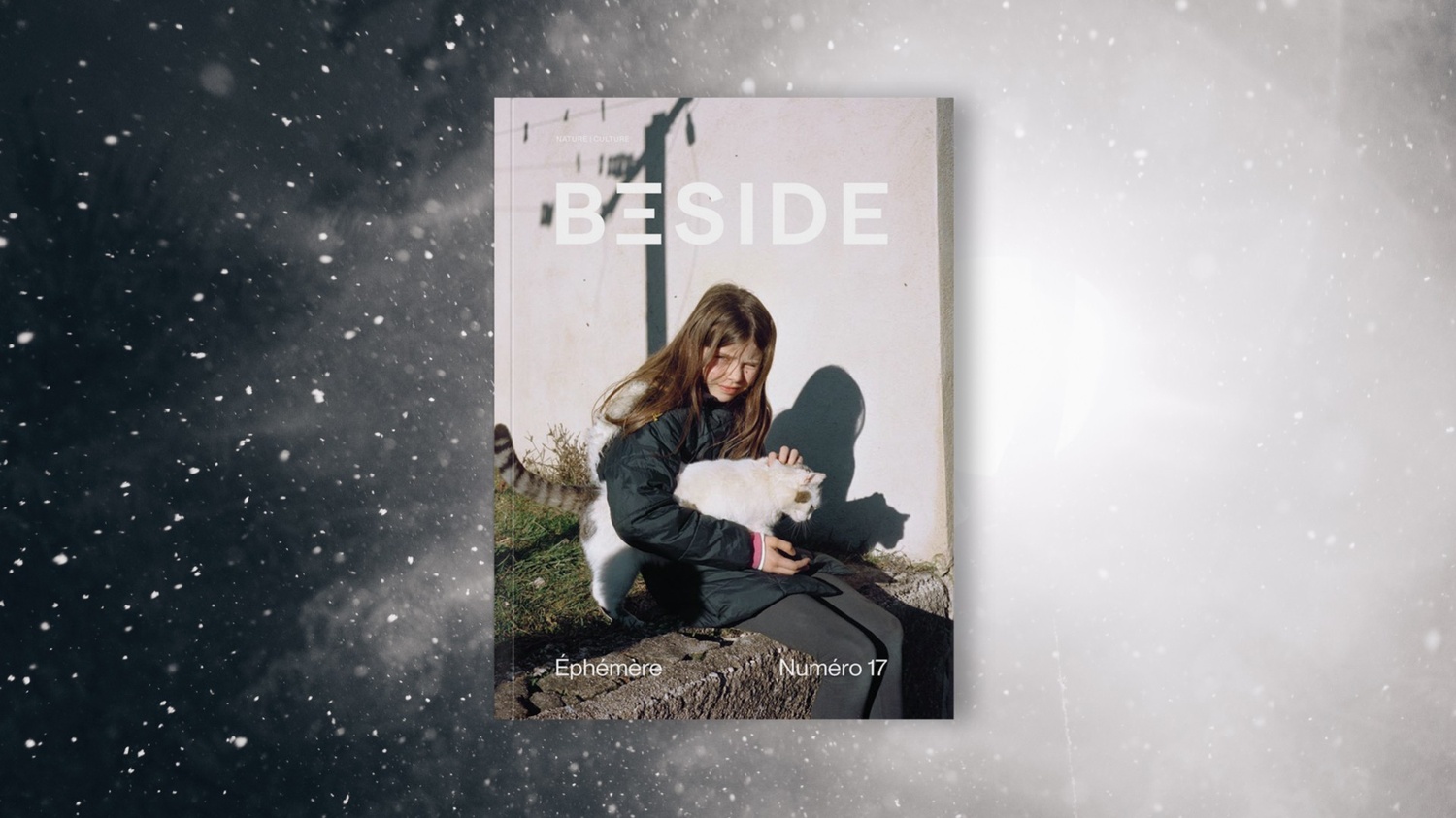

Embrace that everything is ephemeral. Have a good time, rather than following the model of a restaurant: a certain idea of design, of ambiance. The thing that goes beyond, that clashes, even, in an environment—that’s what makes a space authentic.

People often ask, “What’s the cuisine at Denise?” It begins from a human place, with the chef. I feel like everything that comes out of his mind is coherent because it comes from the mind of the same person! The same pair of hands went to the market, cut the vegetables, cooked, and served you. It’s in his mind, in his imagination.

Denise could be an Italian restaurant tomorrow and I would have no problem with that! People will go with it. We’ve already changed identity four times, and people have stayed with us because we don’t try to hide anything.

For me, home is the place where we’re supposed to be ourselves. And that is the quest of a lifetime, to be honest with yourself. Whether through a film for an artist, or a restaurant for an entrepreneur… put your money on integrity, it works every time.